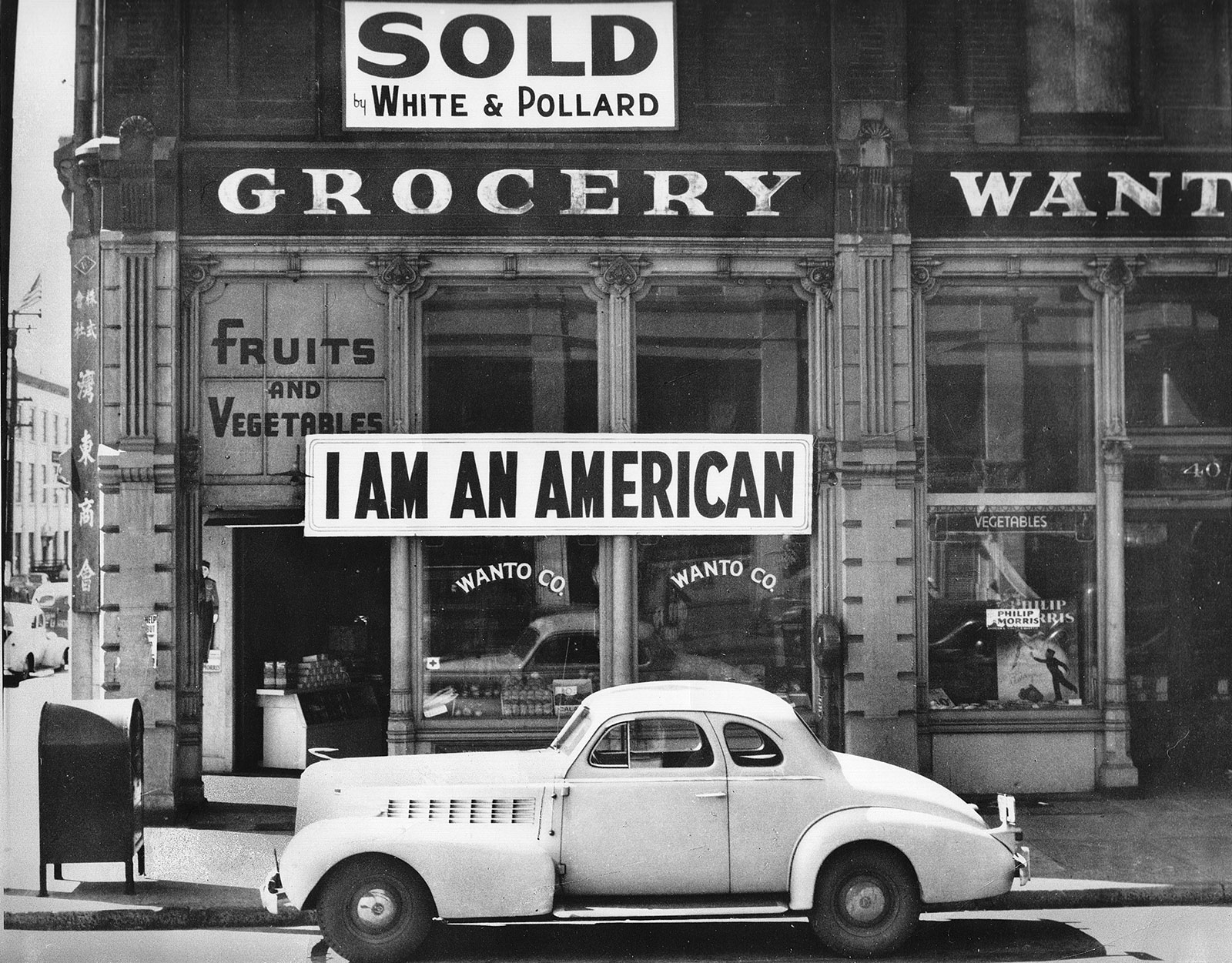

The United States Government between 1942 and 1946, forced the internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans into desert prison camps within the United States without due process. Of those imprisoned, two-thirds had United States citizenship, while the rest were ineligible for citizenship under US law at the time. Most were forced to sell their homes, family plots, and were only allowed to take what they could carry.

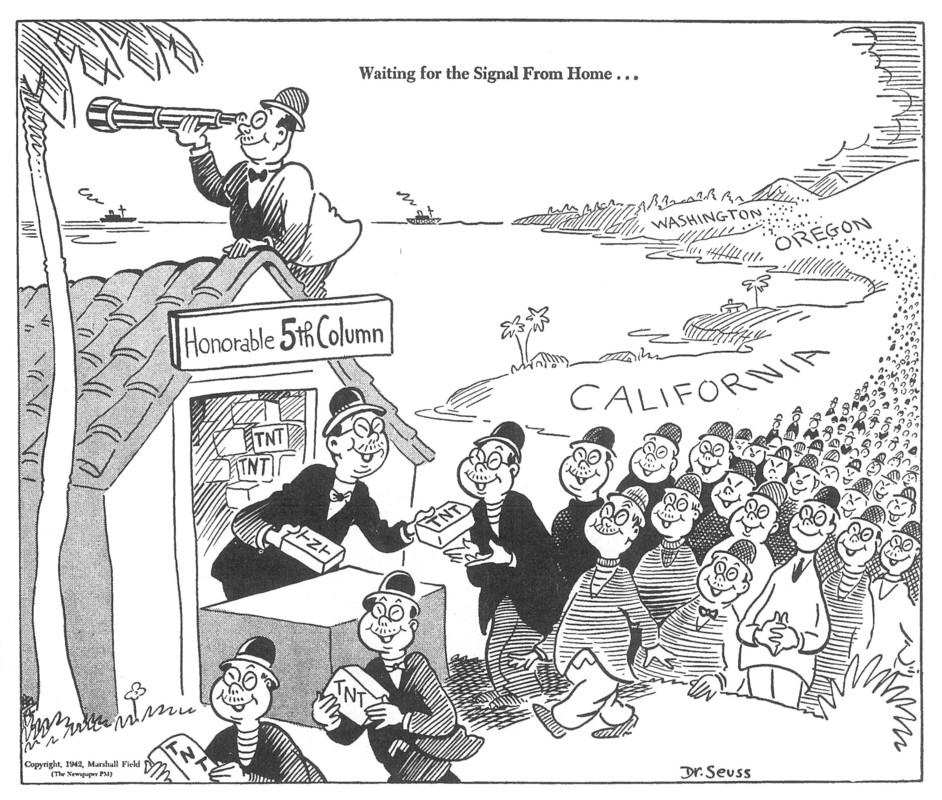

In 1941 US Intelligence report "Munson Report" commissioned by President Franklin Roosevelt concluded that the great majority of Japanese Americans are loyal to the U.S. and do not pose a threat to national security in the event of war with Japan. The report was passed to Roosevelt. It noted that, "The essence of what [Munson] has to report is that, to date, he has found no evidence which would indicate that there is danger of widespread anti-American activities among this population group. He feels that the Japanese are more in danger from the whites than the other way around."

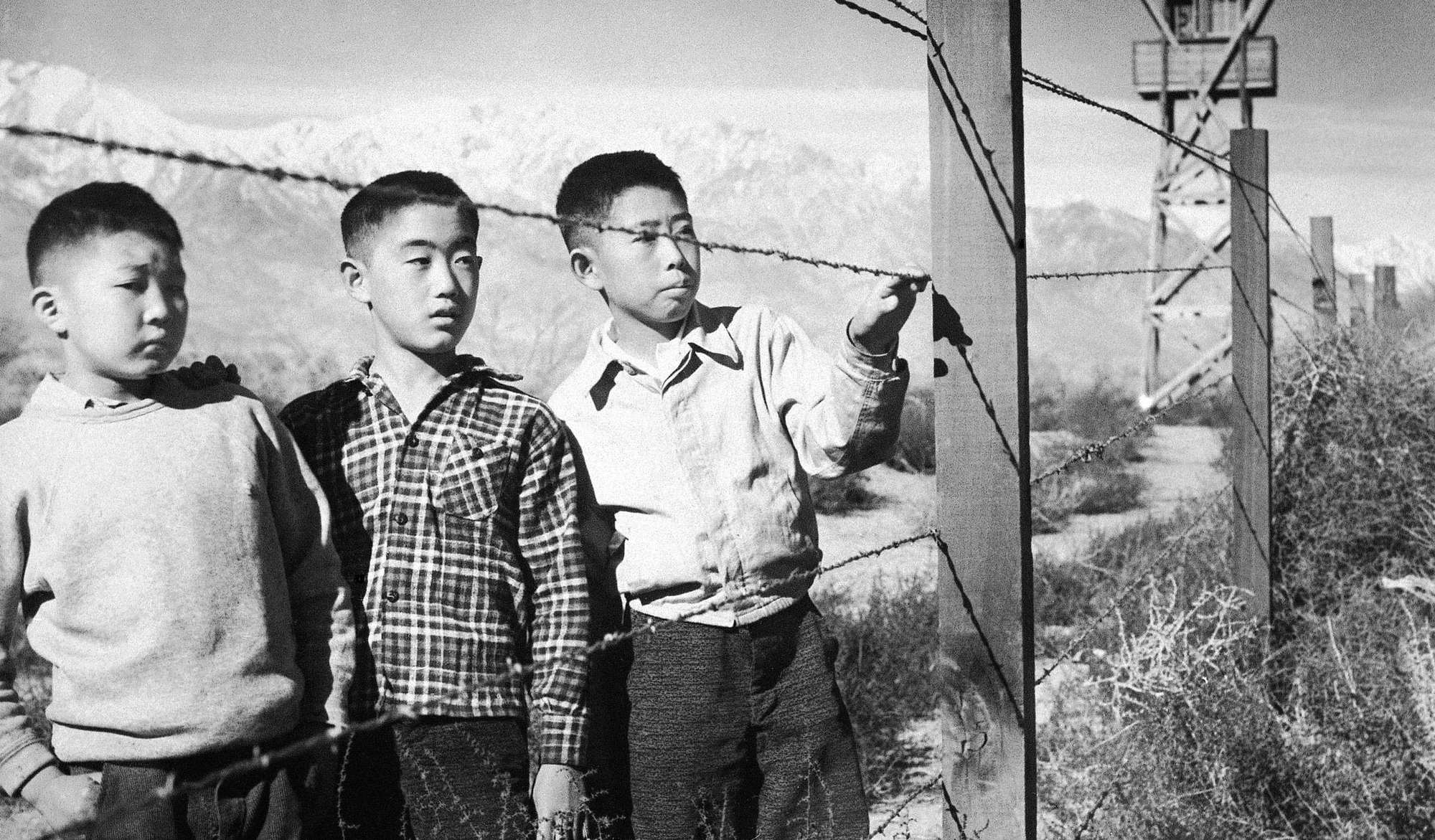

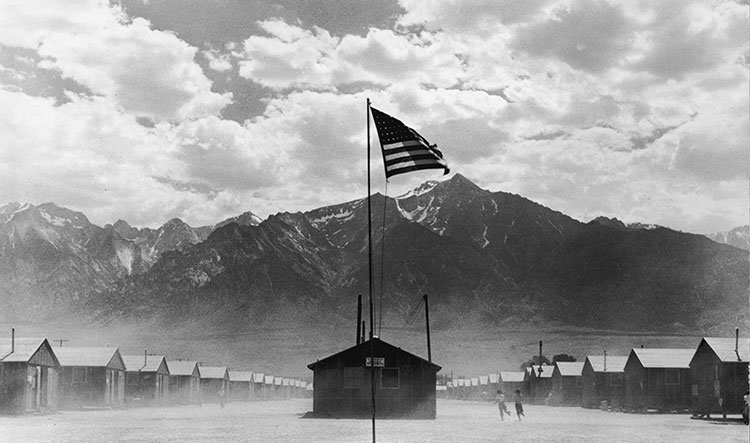

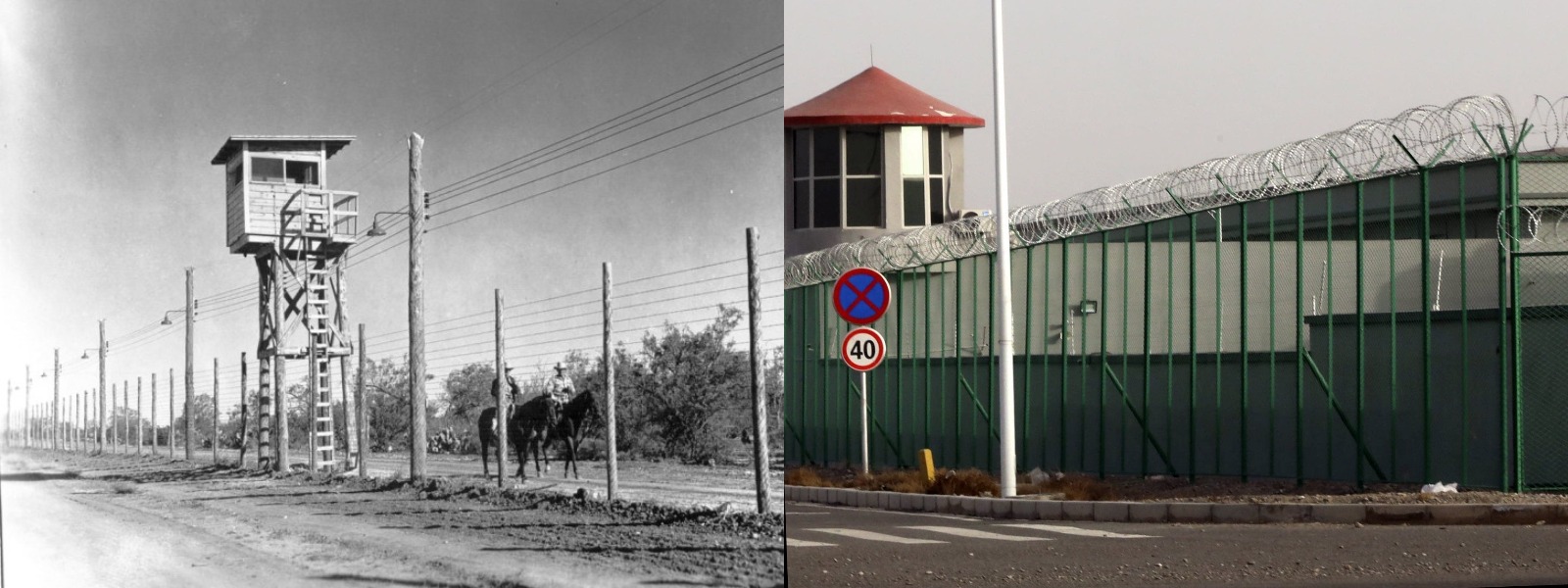

A year after, in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attacks, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the exclusion of any and all Japanese Americans from coastal regions. He performed this action despite evidence presented in the Munsron Report. Executive orders are put in force by the president. They then remain in force until they are canceled, revoked, adjudicated, expire or determined unlawful. Even though it did not specify the Japanese by name, it was quickly applied to virtually all Japanese Americans living in the border regions of California, Oregon, Arizona, and Washington. The US carried out the exclusion and forced removal of all persons of Japanese ancestry into the internment camps. These internment camps were akin to prison camps, surrounded with armed guards and barbed wire. Colonel Karl Bendetsen, the architect behind the program, went so far as saying that anyone with "one drop of Japanese blood" qualified.

It was 1942 when James (Hide Yuki) Nakamura at 11 years old, watched on as the local constable entered his house, and took away his father from him. Soon after, the rest of the family had to abandon their home in Reedley, California and "relocate." Several months later, Agnes Nishida, at 8 years old, alongisde her family, would also be sent to the internment camps.

They had no idea where they were going, or when, if ever, they would be allowed to return. All they knew was that they were leaving, and they could only take what they could carry.

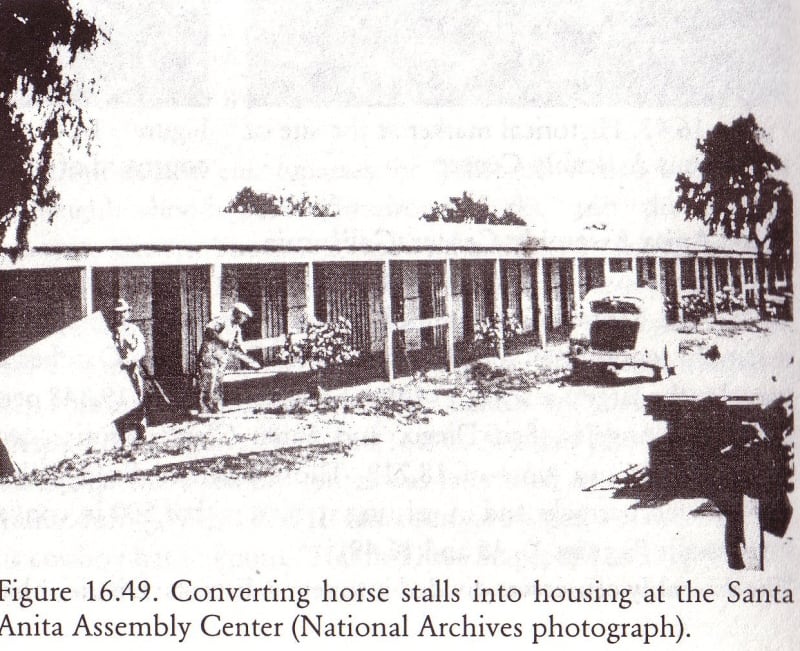

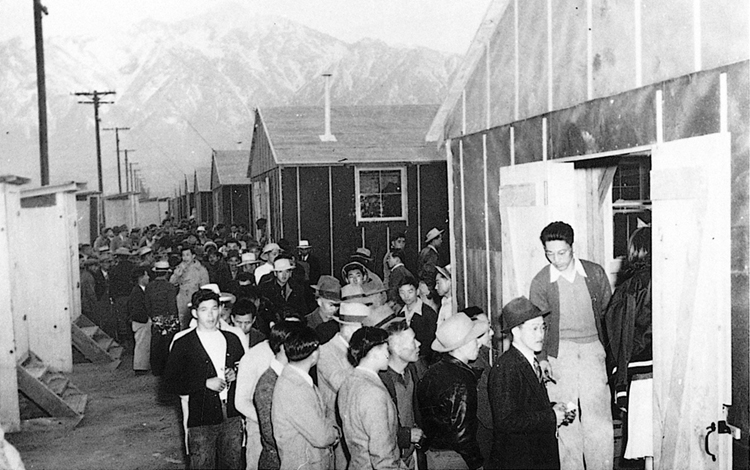

In the months following Executive Order 9066, Japanese Americans were first sent to "assembly centers", which were often horse race tracks or fairgrounds where they were kept until they were sent to internment camps. They had not had any charges of disloyalty, nor were they able to appeal for their loss of property and personal liberty.

Helen Abe was 8 years old when the FBI had tried to take away Helen's mother because she was a school teacher, and place her into the Crystal City internment camp in Texas. They ended up sending the two of them to the Santa Anita racetrack in California. Sam Morri described his experience at the Santa Anita racetrack with his family of 7 as, "We had to live in the horse stalls. They just laid the asphalt right over the poop, everything. It was so hot the legs of the bed would sink in. The smell would really come up from below. We stayed there for 6 months. About 2 months in the horse stalls.Then they built some barracks in the middle of the racetrack."

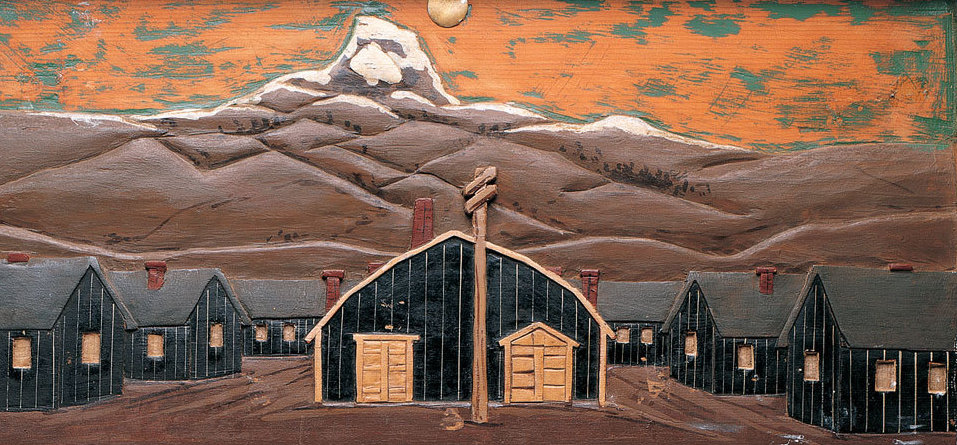

James, Agnes, and their families were incarcerated in Poston, Arizona, which was occcupied by 18,000 internees. The families lived in barracks insulated with light tar paper, the size of a small garage meant for the entire family of 10 people.

"The barracks had bare walls. We had an oil stove, that was the heating, and what we had to do is separate the barrack in half so we have the sleeping quarters on one side and the living room on the other, if you want to call it a living room, it was nothing, maybe a table. We used to hear stories about scorpions coming in, because it was Arizona, we saw some, but not in our apartment. We were overcrowded. In fact, some of us slept outside. The first order of the day after unloading our luggage was to go to the area where they had straw and a cover for a mattress, we stuffed it with straw and that became our mattress.”

"We had 3 meals a day. We couldn't have fancy food, we were lucky to have mutton, people hated it. They made a lot of okazu: cut up meat, zuccini or any kind of veggie, throws it in a pan, maybe some sugar and soy sauce for flavor, then serves it to the family. That's okazu." James' mother, "who had always had a delicate constitution, could not tolerate the camp food and became ill", and passed away two years after they entered into the camp from stomach cancer.

"We didn't pay much attention to the watch towers, but we noticed that even though they were meant to protect us, their guns were always pointed in at us."

"The schools were in barracks. 7th grade on one side, the 8th grade on the other. The teacher had to teach both at the same time. There were caucasian teachers as well. Especially high school level. The menfolk there started building Parker value high school, using adobe bricks so the school was well insulated. They had fairly large classrooms. They built it pretty soon, and we went to Parker Valley High school. We had PE classes as well. There weren't any Japanese language classes. I think they frowned on it because this is still America. When we walked to school we would collect adobe on the bottom of our shoes, we would get a little taller."

"As youngsters, we played softball, basketball and football. My last year I played baseball there. That was fun. We played against other blocks. Just a ball. For basketball they had erected a post, four by four and a hoop. People wanted to play basketball, so that was easy for them to build. At least most blocks had basketball courts."

"They would put a fairly large building on the building that held Oil tank. I guess the federal government provided for that. They would have the projector showing a big screen for everybody to see movies, outdoors. We used to see movies that way. Almost all the movies at the time were black and white, technicolor movies were in the future. White Christmas came up with Bing Crosby, It was winter time when it came out. In the wintertime, some people would build little charcoal tin cans, fill them with charcoal and keep them warm. Eventually, in our camp they built an amphitheatre. They had dances in the mess hall. We didn't dance until the last year there, up until then we could only watch."

While they were still in the internment camps in 1943, the loyalty of Japanese American was questioned in the form of a form that became known as the "loyalty questionnaire." A form given to them with the intent of recruiting them into combat units and judge their "Americanness" or "Japaneseness". On it, there existed two questions that created outrage across those who were incarcerated.

Question 28) "Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attacks by foreign and domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or disobedience to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization"

Question 27 had been a difficult question for those who felt they were being forced into serving a country that was currently imprisoning them. Others felt that they could not risk seeing their family become any more separated than it already had.

Many of the Japanese Americans had been barred from becoming US citizens on the basis of race. Answering Question 28 with a yes and giving up their Japanese citizenship, would explicitly leave them stateless. They could neither hold a Japanese citizenship and return to Japan, nor an American one, in the place they were living.

For many, choosing answers to these two questions created significant rifts between family members, where some couldn't bear to see their children go into the military after seeing so many of their children already separated by the service. Others distanced themselves from these people, not wanting to be seen as disloyal to the cause. It was a symbolic gesture for others, a few who would answer yes, but would then append in the margins "when we are returned our rights as American citizens". 17% of people answered no to both questions as a means of protest. They became known as the "No-No Boys".

Those who answered no to either or all of these questions, were declared disloyal. They were sent to the Tule Lake internment center, which served as a segregation center for 18,000 "Disloyals." Tule Lake, due to its large population of dissidents, was politically active, and this often lead to crackdowns from the military and camp directors.

The director of the camp sought to deport many of these Japanese Americans by prompting them that the camps might close within the year, giving them the option to give up their United States Citizenship. At the time it did not seem like the citizenship had granted them any actual rights. Many feared that if they didn't give up their citizenship, they would be sent out into the surrounding communities and put in harms way at people that hated them for being enemies during the war. However, once they renounced their United States citizenship, a plan was set in action to attempt to deport them back to Japan. A civil rights lawyer from San Francisco challenged this notion, and successfully was able to stall the deportation of the Japanese Americans under the banner of legality, putting up nearly a decade long battle.

Despite denial of their civil rights, many Japanese Americans volunteered for the military service, even against some of their family's wishes. One argument had been that if they decided to not join the fighting force, FDR and people who were for the imprisonment of the Japanese people in the US, would use refusal to join the military as ammunition against them as being disloyal. The Japanese Americans that volunteered were put into the 442nd infantry regiment to fight in Europe. One internee reflected on how he felt the wrongness of being put into the camp, and afterwards, being asked to volunteer for the US army. He explained that joining the military and ending the war quicker, could mean ending incarceration sooner for his father. As they were freeing people in Europe from Nazi concentration camps, they had to deal with the their own families being kept unjustly by the country they were putting their lives on the line for.

Those who went, however, did not hold back fighting for the country they sought to represent. They risked everything, fighting with the infamous motto of "Go For Broke."

To illustrate, in one instance, the 442nd infantry was ordered to break an impenetrable German fortification built into the 3000ft high Apennine Mountains. It had withstood artillery, aircraft, and many other soldiers. The boys of the 442nd unit climbed up the steep back of mountains at night, saying, "If you fall, you cannot yell". Veteran Yoshio Nakamura remembers breaking the Gothic Line, "We climbed up this tremendous mountain in the dark, and surprised the German outpost on the high ground, and that ended the war in Italy."

When a general called the 442nd to assemble for a recognition ceremony, he only saw a few number of men in formation. The general allegedly reprimanded 442nd Lieutenant Colonel Virgil Miller, stating, "You disobeyed my orders. I told you to have the whole regiment." The teary - eyed Colonel looked him in the eye and reportedly said, "General, this is the regiment, the rest are either dead or in the hospital."

Of the 14,000 soldiers who served in the 442nd, two-thirds of them received purple hearts, and 21 of them received medals of honor, the highest individual military decoration awarded by the US government. They also received seven Presidential Unit Citations, the highest award for valor given to a military unit as a whole. The 442nd's effort helped convince Congress to end its opposition towards Hawaii's statehood petition, paving the way for it to become the 50th state.

American civil rights activist Fred Korematsu, with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, challenged the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066, but it was upheld in 1944 by the U.S.Supreme Court in a 6 - 3 decision. The majority ruled that security measures were necessary, while the dissenting justices alluded to, either implicitly or overtly, the role Korematsu’s race played in the decision to incarcerate him.

Justice Frank Murphy dissented, "No adequate reason [was] given for the failure to treat these Japanese Americans on an individual basis by holding investigations and hearings to separate the loyal from the disloyal, as was done in the case of persons of German and Italian ancestry." He further questioned the military's claim of urgency when nearly four months had elapsed after Pearl Harbor before the first exclusion order was issued. A case of imminent danger would have warranted a declaration of martial law. "I dissent, therefore, from this legislation of racism," he stated, "Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life."

Although Korematsu vs. US has never formally been overturned, Chief Roberts in Trump Vs. Hawaii 2018 offered the most powerful rebuke of the result of the Korematsu case at the Supreme Court since the original dissents:

"[...] Korematsu has nothing to do with this case. The forcible relocation of US citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority [...] The dissent’s reference to Korematsu, however, affords this Court the opportunity to make express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—“has no place in law under the Constitution.”

General DeWitt, one of those largely responsible for the incarceration of the Japanese Americans, pronounced "There is a feeling developing, I think, in certain sections of the country, that the Japanese should be allowed to return. I am opposing it with every proper means at my disposal."

Calls began getting made that all Japanese Americans should be stripped of citizenship, reduced in their ability to own land, deported where possible, and prevented from returning. Organizations began sprouting up like the Japanese Exclusion League in Bellevue, Washington and the Remember Pearl Harbor League in Seattle. Earl Warren, after becoming the governor of California, stated, "We don't propose to have the Japs back in California during this war if there is lawful means of preventing it."

When families would return home, they would find that their homes were taken over by other people, vandalised, sold, or their possessions plundered. Their previous jobs were not returned to them on the basis of their Japanese ancestry, bosses telling them to stay home. Landlords were unwilling to provide housing to Japanese American families because they did not want any Japanese people to live with them.

One daughter accounts how her dad took his own life because he was unable to get a job and provide for their family. Another mother remembers taking the train to Chicago with her daughter in search of a new home. However, after inquiring about rent from apartments with "For Rent" signs, she would be told that the place had already been rented. She was forced to live homeless in the city with her daughter. Misleadingly, the War Relocation Authority, who was in charge of helping the internees resettle, ended up using her picture as an incentive picture to encourage other Japanese internees to come take the trip to Chicago to find a home. After the boys from the 442nd came back from serving, they would be denied haircuts even while they were still in uniform. "They wouldn’t give him a haircut because he was Japanese. But he wasn’t Japanese. He was a Japanese American soldier.”

The argument for national security in World War 2 that led to the internment of the Japanese American people has become the center stake in the "re-education" of an estimated 1 million Uyghur people in China. Located in the Western region of China, the country has began implementing layers of surveillance, strict policies and concentration camps for the reported reduction of terrorism and ethnic unity of China. Given the ability of the central power in China to move as quickly as other countries in war time, they are able to move on any notion of fear without a fear of national nor internal backlash. Fuelling the support for their concentration camps with propaganda and surveillance, the government holds tight control on their public unity. Weaving together a deep state of surveillance, they are able to stop activism by keeping people in a great amount of fear of non government approved activities.

It feels all too similar, the concept of safety in the interior being used as rationale for the massive rights being taken away from a minority. The minority is painted to be dangerous, left without the tools to defend themselves, and wondering how they should act.

When the bombs dropped in Pearl Harbor, the horse stalls were still horse stalls. A few months later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, issued Executive order 9066, legally permitting the incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent living on the Western coast of the United States. Two of three of these people were American citizens, yet after that order had been announced, it did not matter. Over the next five years, they were forcibly removed from their homes, and pushed into one of ten "internment" camps. At the time, it had been said to be a war necessity. As the population found out later, it had not been a concern of the investigations into the threat of the Japanese people on the homefront, rather it had been a product of racism, economic threat, and fear mongering. Over the next four years, sitting in swamps to brazen deserts, the Japanese Americans attempted to rebuild their dignity while grappling with questions of loyalty and identity.

In the words echoed by the notes left by those Japanese Americans internned in Manzanaar, "We can never forget what happened. And we will not let it happen again."

If you are interested in learning more, I highly recommend the "Order 9066" podcast which does a great job going through the entire narrative of the internment, from before to far after.

In person, the Manzanar Internment Camp outside of Los Angeles that many people make the short pilgrimage to on the West coast, that has barracks that can be visited as well as a center with artifacts and messages from internees.

Otherwise, if you're looking for stories, I would reccomend picking up a copy of Only What we Could Carry which does an incredible job diving into the experiences of Japanese Americans within the camps.

As a general source for going down specific subtopic rabbit holes, or looking up events, "Densho", a Japanese term meaning ‘to pass stories to the next generation,’ or to leave a legacy, has been set up as a wonderful encyclopedia.

Thank you Sam, Helen, Bob, Fran and Ted for taking the time to sit down with me in Grandpa and Grandma's home in Concord, California, to share their stories from their time in internment. Further thanks to all the people who have written books on the incarceration of the Japanese, built up online resources, and pulled incredible images together that were previously lost. Thank you Grandpa and Grandma for everything you've taught me through conversation and through you living your own lives as a model for us all to learn from. This project is dedicated to you.